History of the Collection: The Baring Family and the Earls of Northbrook

Paintings have lives and can survive hundreds of years. How did they get to where they are now? Art Tracks, Carnegie Museum of Art’s digital provenance project, looks for the answers.

The animation above shows how seven paintings, once part of the Northbrook Collection, ended up in Pittsburgh. Each appearance of a dot represents a painting’s creation and its movement indicates a documented transfer of ownership (provenance), including its time owned by the Earls of Northbrook and their predecessors. The seven red dots highlight the paintings now owned by CMOA and currently on view as part of the companion exhibition, Created, Collected, and Conserved.

Key events from the Baring family and the Northbrook Collection are featured in the timeline at the bottom of the visualization and activated by touch. The following is the full text transcription.

- Beginning of the Baring Dynasty

- Catching the Collecting Bug

- A Portrait of Wealth and Power

- Sir Thomas’s Sale

- Upgrading the Collection

- Collection for Sale

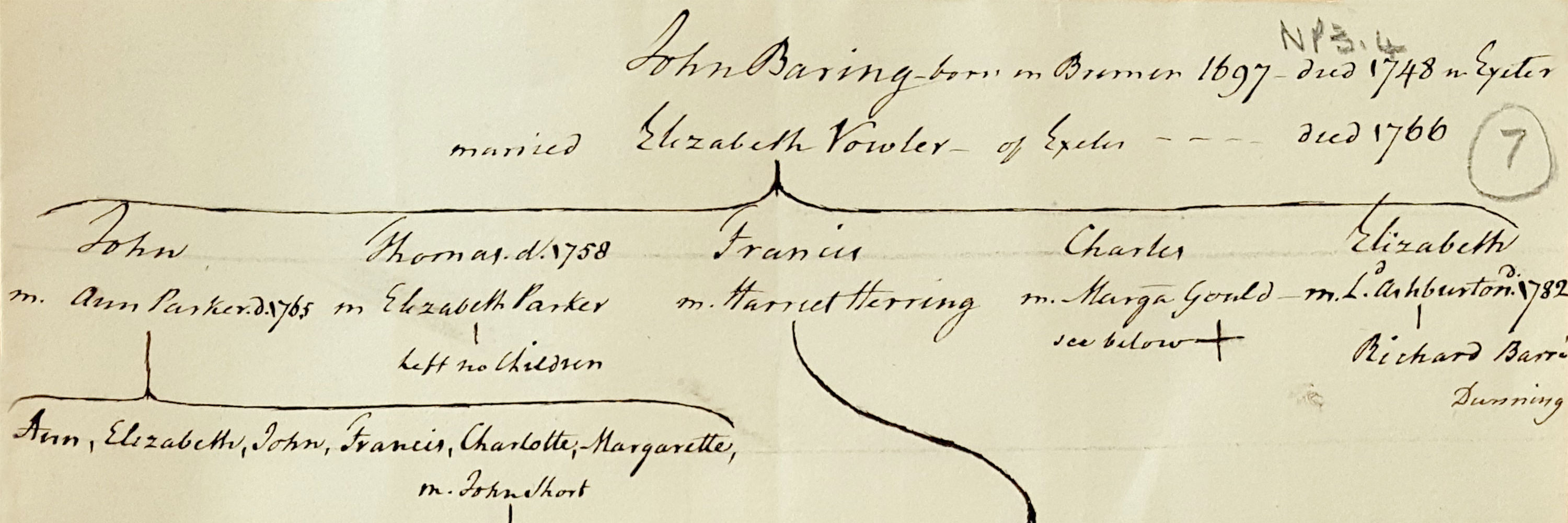

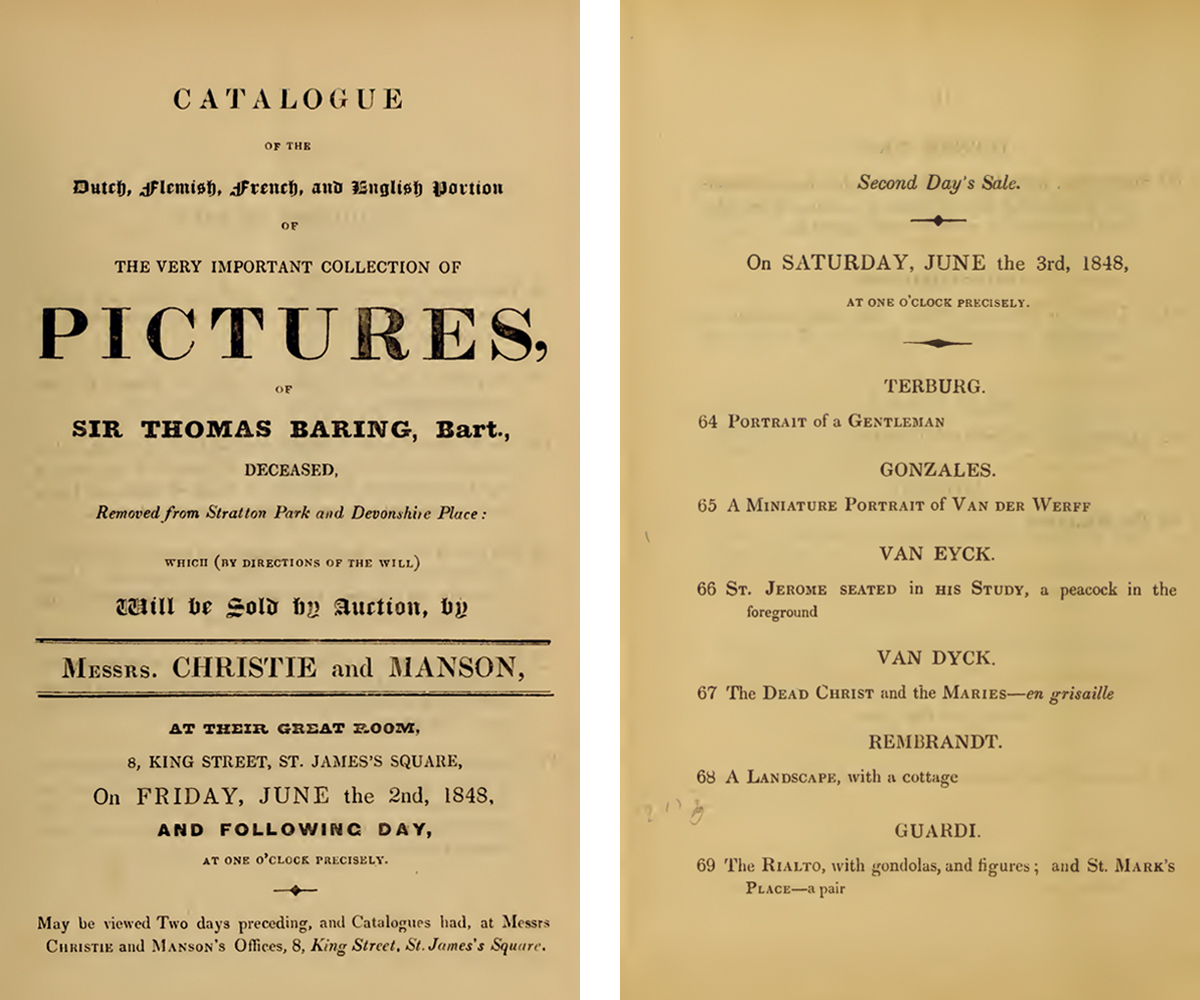

Beginning of the Baring Dynasty

From humble beginnings as wool merchants, the Baring family accumulated great wealth, influence, social standing, and a phenomenal collection of Old Master paintings. By 1818, they had risen to such heights that the Duc de Richelieu, Prime Minster of France, remarked “There are six great powers in Europe: England, France, Prussia, Austria, Russia and the Baring Brothers.”

Their story in England begins with John (Johann) Baring, an immigrant from Bremen, Germany, who settled in the Exeter in 1717. By 1729, he had married the daughter of a wealthy merchant; together they prospered as wool merchants and had five children. The second generation took over the family business and in 1762 they opened a branch in London. There, Francis Baring (1740–1810), expanded the business beyond trading wool and other goods, making several profitable financing deals which earned him a reputation as a leading merchant banker.

By the time the third generation of Barings took over running the bank, the family’s position in international finance was unparalleled. Immense wealth, seats in Parliament, and a series of strategic marriages aided their climb up social and political ladders.

Catching the Collecting Bug

Barings Bank brought great wealth to Sir Francis Baring and enabled his transformation into a true gentleman of means. By the 1790s he was buying property in and around London and a landed country estate, Stratton Park in Hampshire. He also amassed an impressive collection of Old Master paintings to display in his various residences, positioning himself as a man of refinement and social standing. There is no known inventory of Sir Francis’s collection, but there are some indications that the Barings liked to buy and sell in bulk—a quick way to transform any collection.

In 1805, Sir Francis purchased a group of modern paintings from the auction of the famous Boydell Shakespeare Gallery—including Hero, Ursula, and Beatrice in Leonato’s Garden (Act 3, Scene 1 from Much Ado About Nothing) by Reverend Matthew Peters, now part of Carnegie Museum of Art’s collection.

The collection’s greatest strength was in Dutch and Flemish Old Masters. After Sir Francis’ death in 1810, his son, Sir Thomas Baring (1772–1848), sold 86 paintings from this renowned part of the collection to King George IV. Sir Thomas then augmented the collection to suit his own taste, primarily with works by Italian and Spanish masters. His purchase of 24 paintings from a collection of a Paris art dealer Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun steered the collection in a direction more to his liking.

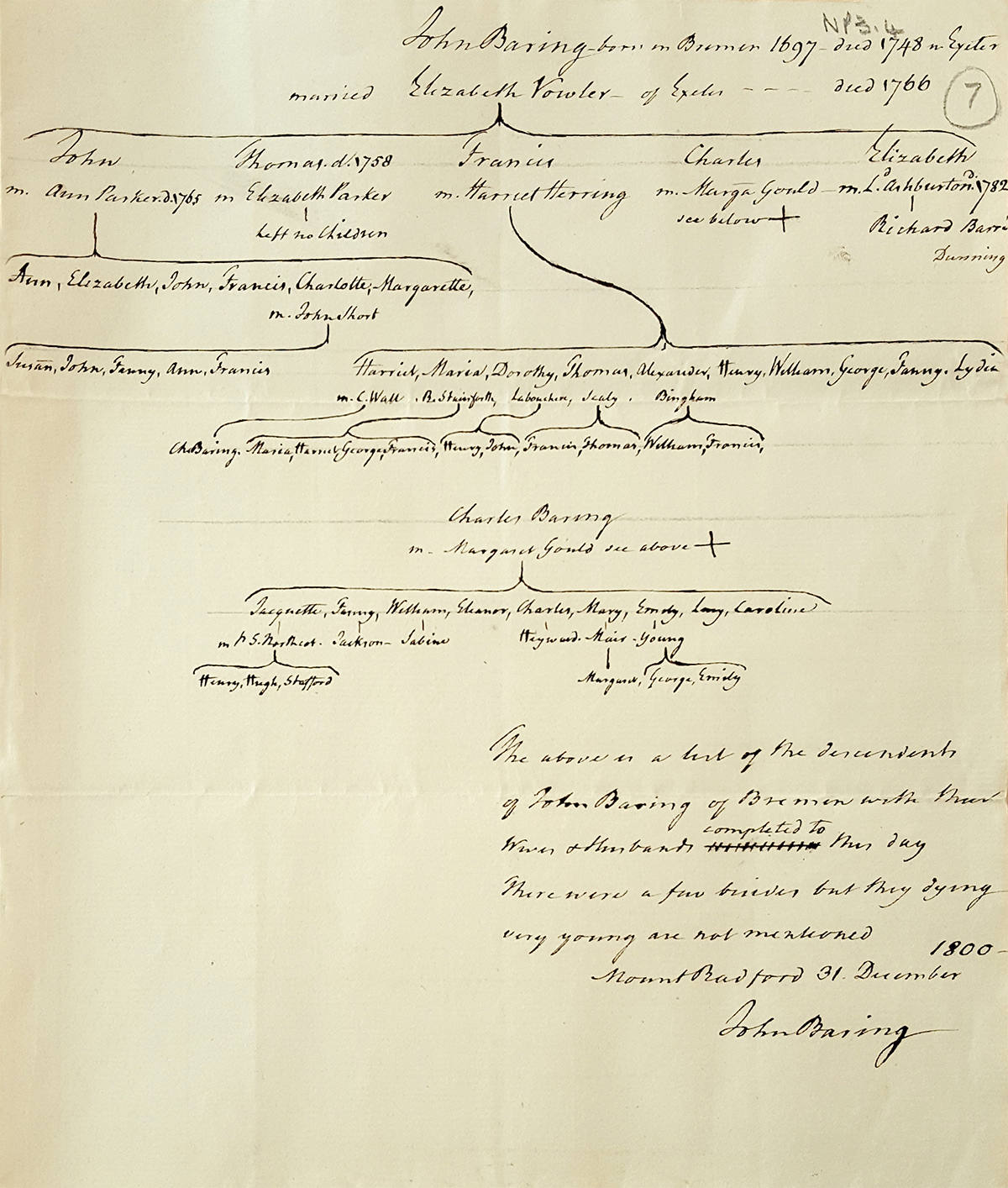

A Portrait of Wealth and Power

In addition to collecting Old Masters, Sir Francis Baring was a patron of contemporary artists, buying “modern” paintings and even commissioning new ones. In 1806, Sir Francis hired the leading British painter Thomas Lawrence to make a portrait of the partners of Barings Bank, in commemoration of his retirement.

Sir Francis, on the left, is seated at a desk with his older brother John Baring, center, and son-in-law Charles Wall, on the right. The sheet in Sir Francis’s hand and the open ledger book pay homage to Hope & Co, the preeminent merchant banking firm in Amsterdam. As close allies, Hope & Co. and Barings frequently partnered on financing deals; together they provided the US government with the money to fund the purchase of the Louisiana territory in 1804.

The original painting was included in the 1807 annual exhibition of the Royal Academy, where it was praised for its dramatic representation of three financiers. The only bit of controversy lay in Lawrence’s decision to depict Sir Francis with his hand to his left ear, alluding to hearing loss at the mature age of 66. The portrait hung in the partners’ room at the bank well into the 20th century and is now in a private collection.

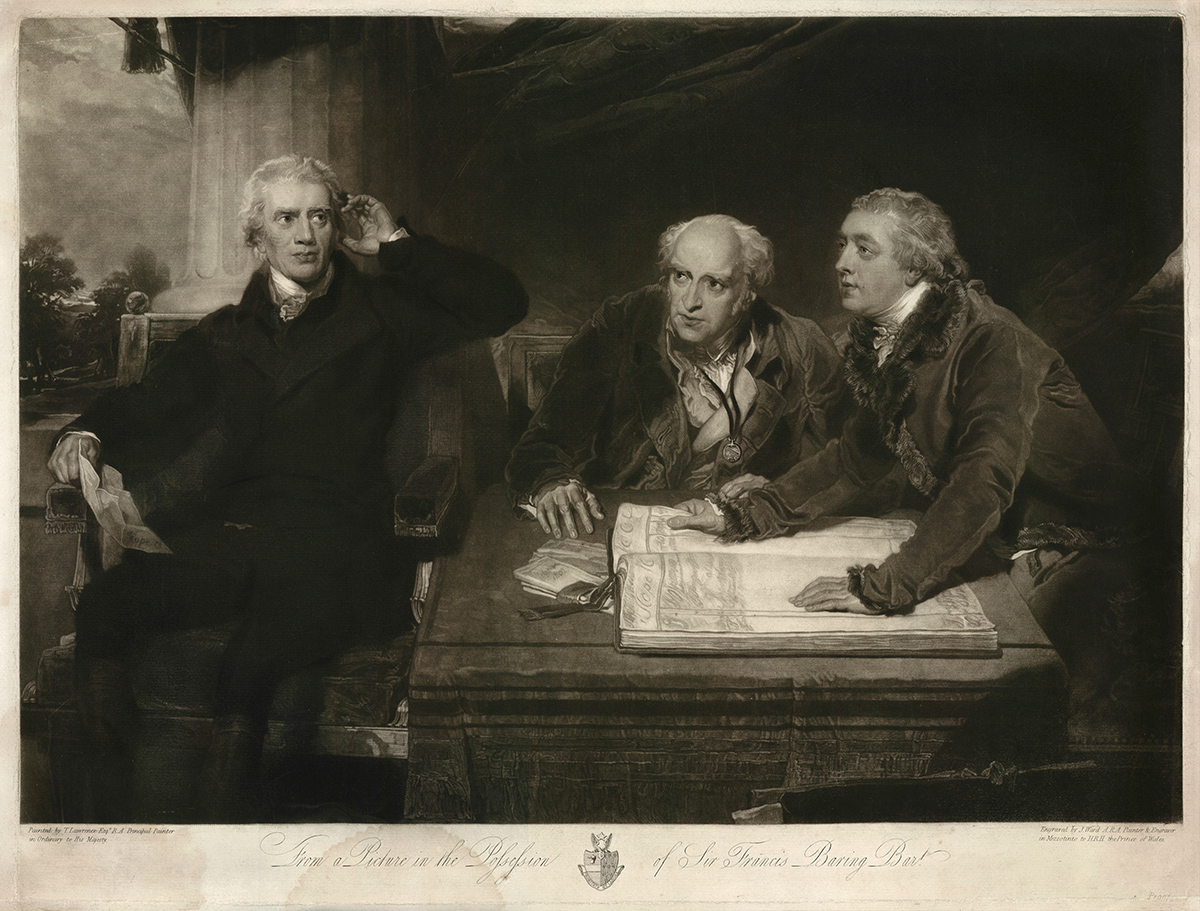

Sir Thomas’s Sale

Sir Thomas Baring’s will dictated that his renowned collection of paintings be sold at public auction. However, Sir Thomas’s son, Thomas Baring, MP (Member of Parliament) (1799–1873), negotiated the purchase of many of the Italian, Spanish, and French paintings from the estate before the sale. As a second son, the younger Thomas did not inherit his father’s title and wealth. But having made his own fortune as a partner at Baring’s Bank, he had the means to keep a significant portion of his father’s art collection intact.

Thomas Baring, MP purchased another batch of his father’s Dutch and French paintings at the two-day sale on June 2 and 3, 1848. For those that got away from him that day, he kept track and purchased them when they appeared in later sales years after. Such was the case of Lot 66, a painting of Saint Jeromein in his study once thought to be a masterwork by the Flemish painter Jan van Eyck. William Conningham bought it from Sir Thomas’s 1848 sale; when Conningham auctioned it off a year later, Thomas Baring, MP snapped it up, reuniting it with paintings from his father’s collection.

Upgrading the Collection

No matter how famous a collection may be, it is not unusual for each successive owner to make their own mark with strategic additions. In 1873, Thomas George Baring, the first Earl of Northbrook (1826–1904), inherited the Old Master paintings collection amassed by his uncle, Thomas Baring, MP. At the time, Thomas George was serving Queen Victoria as the Viceroy to India.

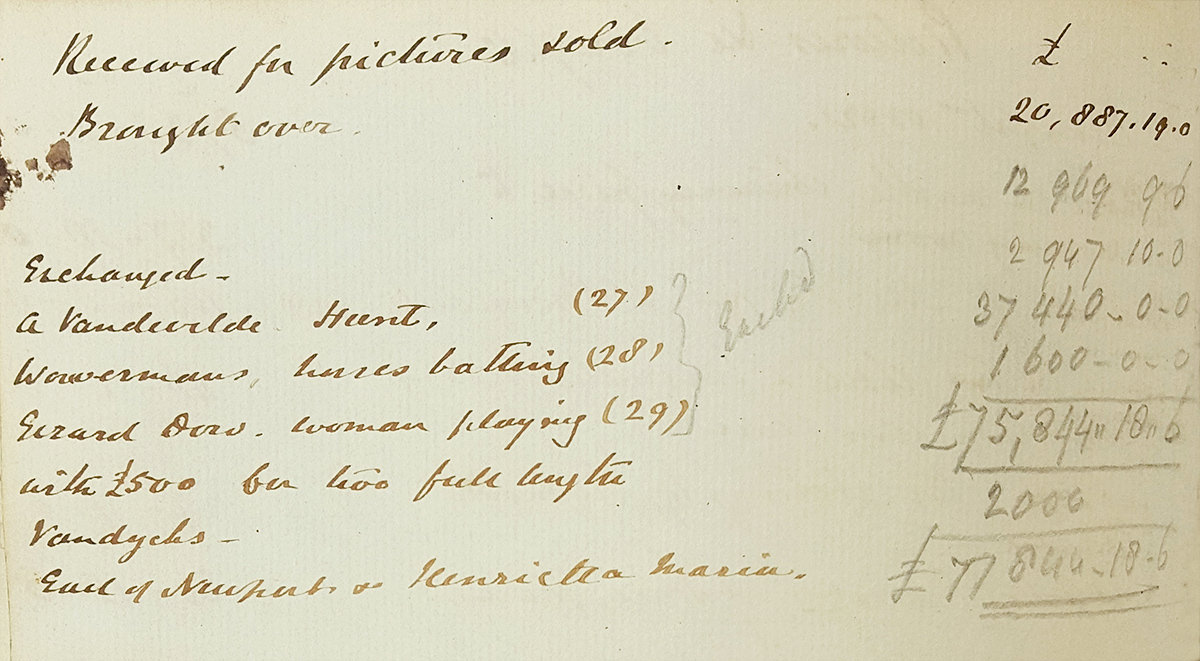

Among the many impressive purchases Lord Northbrook made were two full length portraits by the seventeenth-century Flemish master Anthony Van Dyck.

This page from Lord Northbrook’s household accounts ledger shows his meticulous record keeping. Among other expenses like staff salaries and horses, he recorded this 1881 transaction in the section for “Pictures Bought & Sold”. Rather than buy the portraits outright, he negotiated an exchange of three genre paintings by Adriaen van de Velde, Philips Wouwerman, and Gerrit Dou and an additional £500.

The upgrade had a considerable effect. The spectacular Van Dyck portraits of Queen Henrietta Maria with Sir Jeffery Hudson (National Gallery of Art) and Mountjoy Blount, Earl of Newport (Yale Center for British Art), quickly became some of the most important paintings in the Northbrook Collection.

Collection for Sale

Duveen Brothers, the firm of art dealers, was founded in the 1860s. Active for nearly a century, with branches in London, Paris, and New York, the firm achieved its greatest fame under the leadership of Joseph Duveen, 1st Baron Duveen (1869–ƒ1939), son and nephew of the founding brothers. Under his leadership, the firm became an influential and very successful gateway for the transfer of fine and decorative arts from Europe to wealthy art collectors in the United States.

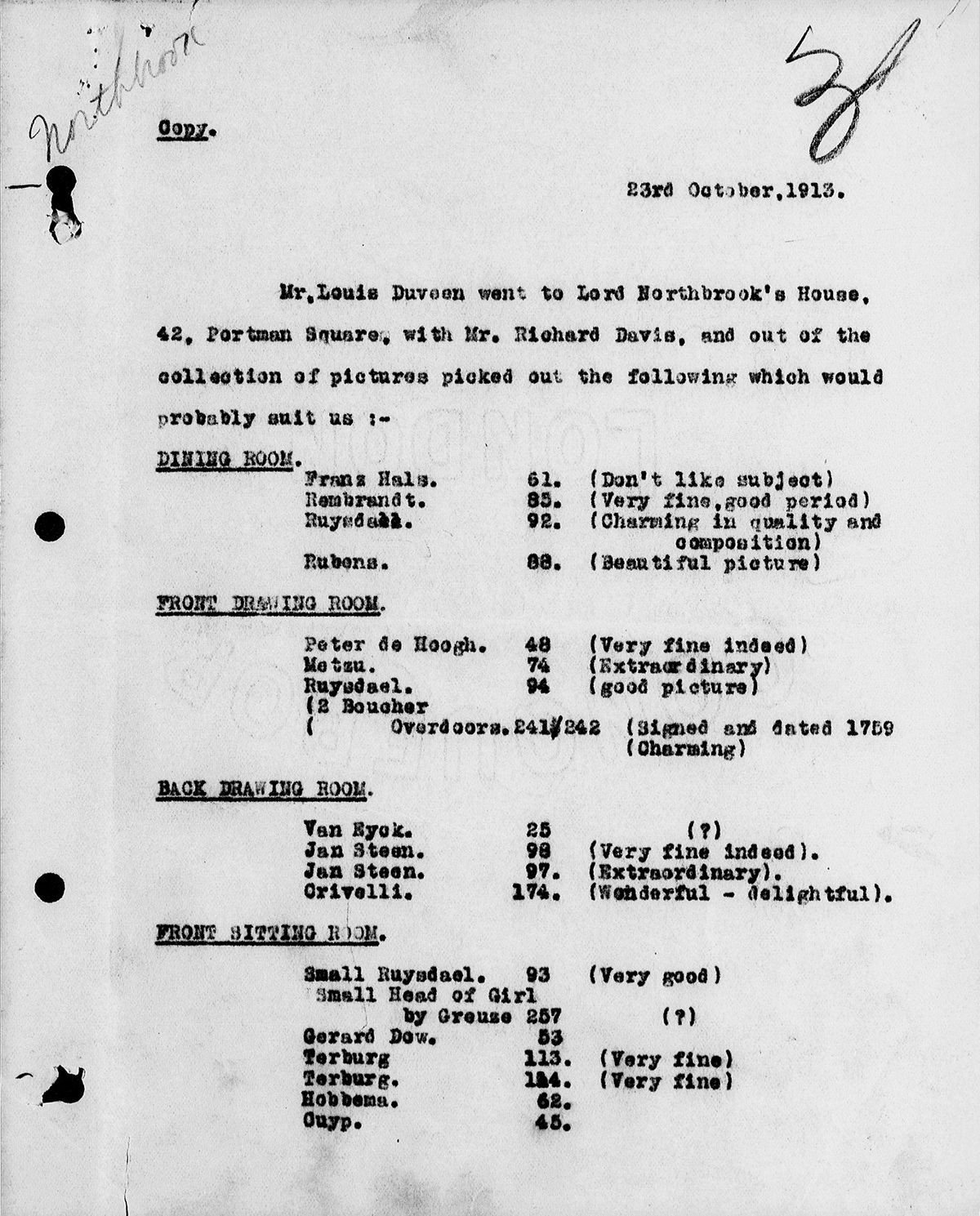

The high quality of the objects in the Northbrook Collection did not escape the discerning eye of Lord Duveen, who was always on the lookout for major acquisition opportunities, which were followed by carefully choreographed sales to his wealthy clientele.

It is not surprising then, that as early as 1913, Duveen representatives visited the Northbrook London residence in Portman Square, to assess the contents and propose potential acquisitions. But Francis George Baring, the 2nd Earl of Northbrook (1850–1929) and his wife were not yet ready to accept an offer for the gems in their collection. So, it took more than a decade to finalize a deal. Finally, in March 1927, Duveen purchased seven of the most important Northbrook paintings, among them a portrait by Frans Hals now at CMOA.